I don't like poetry.

I once made the mistake of confessing this to one of my literature professors while pursuing my degree, which was, of course, in English. He remarked that I had no business in an English program. I graduated anyway.

It's not fully accurate that I don't like poetry. For the most part I don't like poetry. As a literary genre, I find it kind of pretentious—all the more so, the closer to the present that it was penned. On the other hand, I find it works well as a comic medium: the clerihew, for example, the limerick, or whatever you call Ogden Nash's couplets.

That said, there are a handful of poets I can appreciate. Shakespeare, of course. John Donne and George Herbert. Closer to the present, Leonard Cohen and Margaret Avison. And, finally, T. S. Eliot.

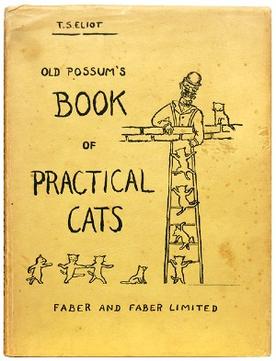

I mentioned a few posts back that I was adopting Kim Shay's 2020 reading challenge this year to help guide my personal reading program. One of the categories on Kim's list is a complete volume of poetry by the same author. When I was brainstorming what I would like to read in 2020, I jotted down "Eliot" next to this one. And, it so happens, the first book of the challenge I completed was Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats.

Most of Eliot's verse is hard to understand (sometimes bordering on incomprehensible) and loaded with classical allusions. C. S. Lewis, whose own aspirations as a poet tended to be more classical, did not understand modernist poetry, and apparently had a particular dislike for Eliot—indeed, they were literary nemeses for many years. He spends three pages in his Preface to Paradise Lost criticizing Eliot's poetic excesses. In a self-deprecating poem titled "A Confession," he singles out his own inability to understand "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock":

For twenty years I've stared my level best

To see if evening—any evening—would suggest

A patient etherized upon a table;

In vain. I simply wasn't able.

Lewis's first post-conversion work of fiction was The Pilgrim's Regress, his allegory of his conversion. At one point in the story, the protagonist encounters three pale men, intended to represent the austere and anti-Romantic modernist poets. One of them, Mr. Neo-Angular, is a caricature based on T. S. Eliot. Practical Cats was published six years later, in 1939. What might Lewis' impression of Eliot have been if he had seen it sooner? (Ultimately, Lewis and Eliot discovered they had a great deal of common ground, and became friends.)

Practical Cats is a short volume (fewer than 50 pages), but that's typical of poetry collections. Unlike his more weighty poems, such as "Prufrock," "The Waste Lands," or "The Hollow Men," this is light verse, originally penned to amuse his godchildren. (Though perhaps the occasional classical allusion slips in—I wonder whether "The Naming of Cats," which reveals that cats have three different names, a common one, a dignified one, and a secret one, parodies the trinomen given to citizens of ancient Rome.)

Practical Cats is a short volume (fewer than 50 pages), but that's typical of poetry collections. Unlike his more weighty poems, such as "Prufrock," "The Waste Lands," or "The Hollow Men," this is light verse, originally penned to amuse his godchildren. (Though perhaps the occasional classical allusion slips in—I wonder whether "The Naming of Cats," which reveals that cats have three different names, a common one, a dignified one, and a secret one, parodies the trinomen given to citizens of ancient Rome.)

Eliot does a wonderful job describing the personalities of cats, including their laziness (Jennyanydots, "The Old Gumbie Cat"), pickiness ("The Rum Tum Tugger"), and thievishness ("Mungojerrie and Rumpelteazer" and "Macavity: the Mystery Cat"). Other highlights include "Mr. Mistoffelees," who can do magic tricks; "Skimbleshanks: the Railway Cat," without whom the mail trains couldn't operate; and "The Pekes and the Pollicles," about a ruckus caused by rival dog factions. But you didn't pick this book up to read about a bunch of stupid dogs.

Famously, Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats is where British rock band Mungo Jerry got their name. It's too bad Mungo Jerry never set the poems to music. Someone really should. In the meantime, if you like light verse and cats, give it a read sometime.

No comments:

Post a Comment